A year in the life of a birch aphid

by

Roger Blackman and Jarmo Holopainen

Euceraphis betulae is a very common aphid on the European silver birch, Betula pendula. In warm dry spells it can build up large populations on the leaves of the birch, and the aphids rain droplets of sticky honeydew down onto anything or anyone underneath.

E. betulae is mainly green in colour but the body of the adult aphids is dusted with a pale bluish wax, which may also form a furry coating on the antennae and legs. In summer all the adults are winged females, and they are very active insects, flying when disturbed.

What are aphids?

Aphids or Aphididae are true bugs, feeding on plant sap which they suck up through highly modified very thin tubular mouthparts termed stylets. Euceraphis betulae belongs to a subfamily of aphids, the Calaphidinae, that live mostly on the leaves of deciduous trees, and to a tribe (Calaphidini) that restricts its feeding to trees in the family Betulaceae, which includes alders (Alnus) and birches (Betula).

Aphids are fussy about what they eat

Aphids of the genus Euceraphis are very particular about the trees that they colonise, and each species tends to restrict its feeding to one species of birch tree. E. betulae lives only on the silver birch, Betula pendula.

The European silver birch is an attractive tree with ornamental varieties that grow easily in a variety of soils, and it has been widely planted in parks, gardens and town squares, not only in Europe but in other parts of the world, particularly in North America, Australia and New Zealand. Euceraphis betulae has been introduced on silver birch to all these places. In North America it still feeds only on European silver birch and ignores the native North American species.

In Europe there is a second common native birch species, the downy birch Betula pubescens, which is closely related to the silver birch but tends to occur in damper soils and is commoner in the north. Downy birch is colonised by a different, very closely-related Euceraphis species, E. punctipennis.

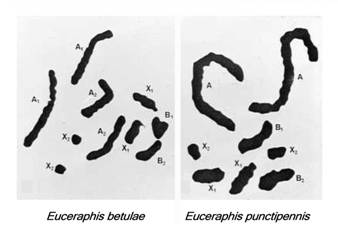

E. betulae and E. punctipennis are very difficult to tell apart and for many years they were not recognised as separate species. Differences in their chromosomes helped to make the distinction between them. E. betulae has two pairs of the chromosomes called autosomes (A1 and A2), whereas in E. punctipennis these have fused into one long pair (A).

In North America and eastern Asia there are other Euceraphis species that live on the birches and alders native to those regions.

In Europe there are 12 other aphid species that feed on birch trees, most of them in the same aphid subfamily as Euceraphis, but in other genera. Aphids of the genus Euceraphis are recognisable by the combination of relatively large size (body 3-4 mm long), pale green colour with bluish wax dusting, and the fact that all the adults in spring and summer populations are winged.

Aphids can produce young without mating

Like other aphids, all the birch aphids that you see through spring and summer are female, and give birth to live young without mating (parthenogenesis), producing clones of themselves. This method of reproduction enables them to build up large populations very quickly on the nutritious young spring growth. Euceraphis can first be found in early April, as young nymphs that have hatched from overwintering eggs feeding on breaking buds and expanding leaves.

In a few weeks these nymphs have developed into adults:-

By June their offspring are themselves producing young, so by the time the tree is fully in leaf there may be very large numbers of aphids.

Remember that all these aphids are female, giving birth parthenogenetically to their young, without being mated. They are also viviparous; their young are born alive and active, not laid as eggs.

When the leaves are mature they are less nutritious, so during July and August Euceraphis stops producing young. Then in September, when the food accumulated in the leaves throughout the summer starts to be broken down and translocated to the roots of the tree prior to leaf-fall, the sap becomes full of nutrients again and a new generation of winged adults develops. These prefer to feed on the most nutritious, yellowing leaves.

All change in autumn

The next generation of Euceraphis, becoming adult in October-November, looks completely different. It consists of winged males and wingless brown egg-laying females.

When the female has mature eggs inside her, mating occurs and she then lays her eggs on the birch twigs.

The eggs are bright orange-yellow when first laid, but soon become shiny black, and are then resistant to the cold of winter.

The winter is passed as an egg, and in spring the life cycle of the birch aphid starts afresh.

So why have sex?

If female aphids can get along so well through spring and summer without males, why have sex at all?

In the eggs that develop inside these females, the chromosomes have undergone meiosis, a process in which they pair and exchange parts, generating new combinations of genes. By having this annual sexual generation in autumn, after months of clonal reproduction, E. betulae ensures that the next year’s aphids have the genetic diversity needed to survive another year.

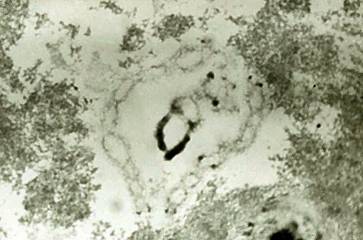

This photomicrograph of the inside of an ovary of E. betulae shows the nucleus of an egg with chromosomes at the stage of meiosis called diplotene, when pairing and crossing-over occurs. The “chains” visible in the photograph are paired chromosomes, and the “links” in the chains are the points of crossing over between them (called chiasmata). Thus we are here looking at the actual process by which genetic diversity is created.

References

Blackman, R.L. 1976 Cytogenetics of two species of Euceraphis (Homoptera, Aphididae). Chromosoma (Berl.) 56: 393-408.

Blackman, R.L. 1977 The existence of two species of Euceraphis (Homoptera: Aphididae) on birch in western Europe, and a key to European and North American species of the genus. Systematic Entomology 2: 1-8.

Blackman, R.L. and De Boise, E. 2002 Morphometric correlates of karyotype and host plant in genus Euceraphis (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Systematic Entomology 27: 323-335.

Holopainen, J.K., Semiz, G. and Blande, J.D. 2009 Life-history strategies affect aphid preference for yellowing leaves. Biology Letters 5: 603-605.